Through the last century, scientific psychology has seen an explosion of research and theories in the field of intelligence and IQ tests. Although many people think that the field of intelligence is all mambo-jambo, a myth like many others that we explain in our fun article about intelligence myths, the truth is that there are few areas in psychology with such a huge amount of work. But even after so much research, the enormous complexity of our human intelligence has left many question marks to be answered.

A very recent theory of intelligence, however, is bringing together several previous theories and findings and has already collected a lot of scientific evidence in the last few years. It is called the Cattell-Horn-Carroll model of intelligence, also called the CHC theory, and is the most proven theory of intelligence to date.

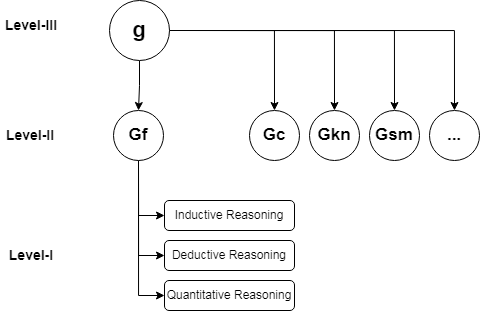

As the intelligence researchers McGrew and Schneider explain, the CHC model proposes that intelligence has three levels: with intelligence (level-III) made up of several broad abilities (level-II) like short-term memory or visual processing, which are themselves made up of narrower abilities (level-I abilities). Probably this reminds you of Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, which is similar in the fact that both propose several intelligence abilities, but the CHC model is the organization of abilities that has received the biggest amount of study and proof.

In this article we will dive in-depth into how the first intelligence theories evolved into the current CHC model, what specific abilities make up intelligence according to CHC theory, and finally what limitations and future lines of research could await us.

How CHC theory originated

Formulating a valid theory of how intelligence works and how its components are organized is very important. Having a proven theory about the structure of intelligence not only allows researchers to have a common framework under which to work and understand the mind, but it also allows clinicians and school psychologists to make accurate assessments and in turn good decisions.

Hence, classifying the abilities that make up intelligence has been a primary goal in the field since the research on intelligence started one century ago. We cannot get into every detail of its development, as that would surpass the goals of this article, but if you want to you can learn the full history of intelligence and IQ tests in our article devoted to it. Now we will focus only on the developments that led to CHC theory.

One of the first intelligence researchers was Spearman, who proposed the famous two-factor theory of intelligence, with general intelligence on the top, and any other ability beneath and influenced by it.

His disciple R. Cattell was of a different opinion and thought that general intelligence was not good explaining an adult’s intelligence. He was a very strong researcher and after twenty years of statistical work, Cattell published in 1943 a new theory with a lot of evidence and great impact. He suggested that intelligence was made up of two factors, fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. The first one represented the raw capacity and speed in learning, while crystallized intelligence reflected the knowledge already acquired.

Cattell had studied profoundly how the different capabilities evolved, peaked, and declined as persons aged, and discovered that the decline in the speed of learning did not go hand in hand with less “power” of intelligence or know-how for activities. Both fluid and crystallized intelligence were highly related, unsurprisingly since according to his theory a higher fluid intelligence would in turn make any learning effort more impactful and allow a greater knowledge gain.

It would be his own disciple Horn, who in his dissertation proposed merging Cattell’s theory with the theory of independent abilities of Thurstone. The so-called “extended Gf-Gc theory” first meant adding to fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence other abilities such as visual perception, short-term and long-term memory, and processing speed. But as time went by, he and other researchers proposed several more factors and rejected Spearman’s idea of the existence of a general intelligence factor.

In 1993, Carroll published the absolute masterpiece “Human Cognitive Abilities” in which he reanalyzed more than 400 intelligence studies and concluded that the extended Gf-Gc theory was correct but needed modifications, he proposed a three-level structure of intelligence and described with thorough detail all the narrow abilities that composed each one of the different level-II broad abilities. He also tried to justify theoretically that a general factor of intelligence indeed existed. Carroll’s work is considered the beginning of the current CHC theory, which in its recent shape was laid out by McGrew in 1997.

The abilities of the CHC model of intelligence

As we said before, according to the CHC model of intelligence, the structure of intelligence is characterized by having three levels. At the very top (level-III) we find general intelligence (also called “g”) that represents the global intelligence ability. There is a lot of debate as to whether “g” is only a statistical average or if it represents a global level of skill that exists. In our opinion, one way or the other, it is still valuable to measure it to have a summarized overview as long as the person is measured holistically.

At the second level (level-II) we find the so-called broad abilities, which are a group of interrelated narrow abilities (level-I). This last group of narrow abilities is the last level and they were defined by Carroll as “greater specializations of abilities, often in quite specific ways that reflect the effects of experience and learning, or the adoption of particular strategies of performance’”.

The fact that narrow abilities within a broad ability are related is what justifies them being grouped together in a superior level as a broad ability. The same reasoning applies at a superior level. The broad abilities at level-II are not fully independent but correlated to different degrees, and that is why they can be grouped in a general intelligence factor.

For example, inductive, deductive, and quantitative reasoning are different but related to narrow abilities that together make up fluid intelligence. Usually, each narrow ability is tested with a specific task in an IQ test. But sometimes there is one task with questions of each type of reasoning to evaluate the broad ability of fluid intelligence altogether in one task.

Next we will see the full list of 17 broad abilities and in some of them we will indicate examples of its narrow abilities. For this description, we will follow researchers Flanagan & Dixon (2014) and Schneider & McGrew:

- Fluid intelligence (also called “Gf”): refers to the ability to focus attention and solve novel problems through reasoning, learning and pattern recognition. The narrow abilities that make up fluid intelligence are inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning and quantitative reasoning.

- Comprehension-Knowledge / Crystallized Intelligence (Gc): is the depth and breadth of knowledge valued in one’s culture. Some of its narrow abilities are general verbal information, language development, lexical knowledge or listening ability, among others.

- Domain-specific knowledge (Gkn): refers to the level of specialized knowledge that a person has in the field in which it has focused the most.

- Short-term memory (Gsm): is the capacity to store and utilize information maintained in awareness during a very short period of time, usually seconds. Its narrow abilities are memory span (simple repetition) and working memory capacity (ability to store and manipulate the information).

- Long-term memory (Glr): the same as short-term memory but for longer periods of time, from minutes to years. It has many narrow abilities, like associative memory, meaningful memory, free-recall memory, ideational fluency, and so on.

- Visual processing (Gv): is the capacity to solve visual problems through visual perception and analysis, imagination, simulation and transformation. Its narrow abilities are visualization, speeded rotation, visual memory, spatial scanning, or perceptual illusions, among other.

- Processing speed (Gs): is the speed at which a certain task can be done repetitively. Its narrow abilities are writing speed, reading speed, perceptual speed, rate-of-test-taking or arithmetic facility.

- Reaction and decision speed (Gt): is the speed at which simple decisions are taken. Its narrow abilities are simple reaction time, choice reaction time, semantic reaction time, semantic processing speed, mental comparison speed and inspection time.

- Psychomotor speed (Gs): is the speed and fluidity of physical body movements. Some of Its narrow abilities are speed of limb movement, writing speed, speed of articulation, and movement time.

- Other broad abilities which we will not see in detail but which the model also considers are: Auditory (Ga) Olfactory (Go), Tactile (Gh), Quantitative Knowledge (Gq), Reading & Writing (Grw), Kinesthetic (Gk) Psychomotor (Gp).

A great way to understand the hierarchical structure of intelligence abilities is to see them graphically. Below you can visualize in english the structure showing fluid intelligence and its narrow abilities at level-I plus other level-II broad abilities as an example:

IQ Tests based on CHC theory

Since most intelligence tests had not been developed under the support of a global overarching intelligence theory, something that both the Wechsler Scales and the Stanford-Binet tests suffered from, there was not much initial interest in CHC theory. That would change after the creation of the Woodcock-Johnson-III Intelligence Test, published in 2001, which became the first intelligence battery fully grounded on CHC theory. Obviously, the WJ-III fits very well with CHC theory.

But the growing evidence supporting CHC started to put pressure on test developers to analyze the fitness of their tests to CHC and even to adapt their tests to it. Also, researchers performed cross-battery analysis (by using two different tests with different theoretical orientations and merging their results together for analysis) to see if the joint results further supported the theory and obtained positive results.

So now not only do the Wechsler Scales or the Stanford-Binet Test explain in their technical manual how their tests fit to CHC, but the tasks of the tests have been modified in their last versions to fit better with the theory. Other relevant tests like the DAS, the CAS, the KBAIT, and the Reynolds Intelligence Test have been found to fit as well to CHC theory, as researchers Keith & Reynolds (2010) explain.

Limitations and future development

As we have seen with the sheer number of abilities that CHC proposes, it is a complex theory, and not all of its parts have been equally researched and proven. Its first limitation is that we need studies with bigger sample sizes that are more representative of the general population. That would make the results more significant and the theory support stronger.

Second, there has not been enough exploration of rival models, and as McGill and Dombrowski explain in a paper critically reflecting on CHC, too much of the recent supporting data now comes mostly from the Woodcock-Johnson-III, which as we said before is a test developed upon CHC theory, so the conclusions can be pretty tautological.

Third, crystallized intelligence is an important ability and yet it seems to be a very elusive concept that encompasses a mix of verbal skills, knowledge, school achievement, and culture. A more clearly defined separation from the rest of abilities is necessary.

We think that in the future the biggest innovations to the theory will come from the abilities that have been added last, such as the kinesthetic and psychomotor abilities, which have been barely studied as potential intelligence abilities up until now.

Perhaps more importantly, we think that emotional intelligence will sooner or later find a bigger role and acceptance within the model. For now, it is only considered in a restricted manner as “Knowledge of behaviors”, a narrow level-I ability within the broader ability of domain-specific knowledge. We have no doubt that it will grow in weight.

Summary of the CHC model

We have covered thoroughly the basics of the most validated intelligence model, the CHC model. After reviewing the previous models that led to its current incarnation, we saw the full list of abilities and some examples of the narrower abilities that make up each of them.

The list of broad and narrow abilities is already big and growing, which is understandable since humans are very complex beings. Probably, the model will see some modifications in the future, especially with a bigger relevance of emotional intelligence, and maybe some simplifications that still maintain the predictive power of the model.

It is more clear than ever that science supports the idea that intelligence is not only about complex pattern recognition, mathematics, and abstract reasoning, even if they are perhaps the most relevant skills explaining it and the ones most important to measure because of their predictive power. But it includes many other abilities as distinct as visual, or auditory processing, speed, memory or psychomotor abilities. In the end, when we talk about intelligence we refer to the adaptation to the environment, and humans have adapted in an incredible myriad of ways.

.png)

.png)