We tend to think that the more we have of something, the better. More money, better looks, more friends, more education, more free time…who would not want all of that right? Yet at the same time, we do suspect that too much of something also carries risks. Someone super handsome or rich could be loved only for their looks or their money. Someone very educated could feel overrun by expectations. And so on.

But who of us would not want more intelligence, either cognitive or emotional? And as much as possible? Especially when it has been proven by science again and again that having more intelligence means more chances of success in different areas of life! Well, like with the first desires we talked about, it is necessary to tread with caution.

Humans are the pinnacle of evolution, aren’t they? While it is true that some cognitive and emotional skills of humans are vastly superior to that of animals (as we explain in our article about the intelligence of animals), there is a dark side to the story that has barely been told. A darker side with the summary that follows. Our human race suffers a disproportionate amount of mental disorders in comparison to other animal species, like for example monkeys.

Our body and mind are the product of an evolution orchestrated through a careful equilibrium between many different biological, cognitive, and behavioral components. If one thing changes, several others should accompany it. An improved adaptation that is considered useful in one context usually carries new risks and tradeoffs. A great example is the human throat and in particular its epiglottis. Our epiglottis allows us to vocalize in more complex ways than a chimpanzee could ever do. But the risk of choking is much higher in humans, who cannot eat and breathe at the same time unlike chimpanzees (or the food or drink could easily get in the lungs).

The causes of the disproportionate amount of mental disorders in the intelligent human species have always been a matter of scientific debate, and in the last decades, we have begun to unravel the mystery. In this article, we will dive into how and why cognitive and emotional intelligence, both in low and high levels, is associated with physical and mental disorders.

Is more intelligence related to better health?

The first simple rule that scientists found was that having a lower intelligence was associated with more health problems, whereas having a higher intelligence gave a person better chances of well-being.

For example, the team led by Harvard University professor Koenen found in a study that 15 more points of IQ in childhood (for example from a score of 85 to 100 IQ) entailed between 20% to 40% less probability of developing as an adult a disorder such as depression, anxiety or schizophrenia.

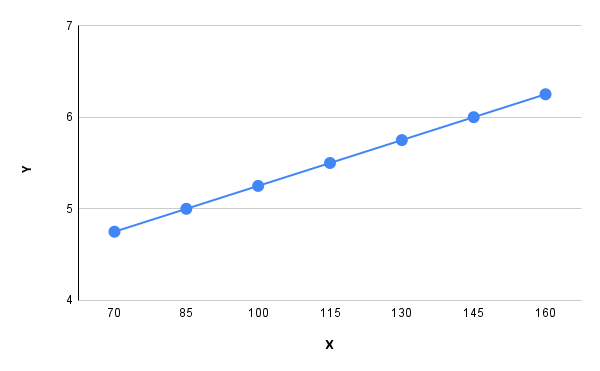

We could call it a linear relationship between IQ and health (more intelligence, better health). Let us see it in a graphic (with X as IQ and Y as probability of enjoying good health).

However, the results from some studies which focused on gifted people were creating confusion in the field. Professor Lauren Navrady from the University of Edinburgh and their team found that a higher IQ meant higher chances of depression, or the French team led by Kermarrec found that children with an IQ of more than 130 suffered a higher risk of anxiety.

Although some researchers have criticized the field for lacking enough participants to draw serious conclusions from, all studies in psychology have limitations. We actually think that both types of studies reached correct conclusions because they had found two parts of a more complex phenomenon.

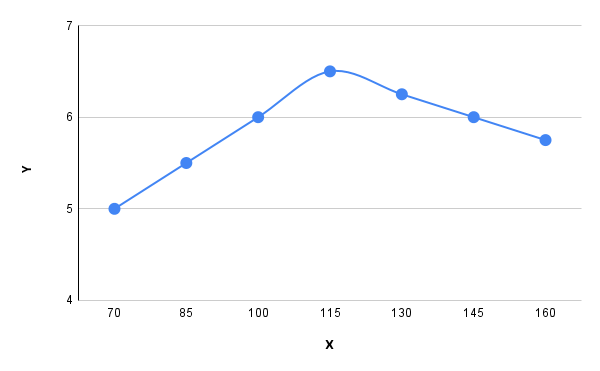

As the team led by prof. Karpinski has proposed, we think that the relationship between intelligence and health is actually curvilinear, such as that having lower intelligence usually carries more risks, and having higher intelligence is more protective, but only until a certain threshold where it starts to turn around so that very high IQs will have a higher probability of mental problems. An effect whose potential causes they explain in a theory called “hyperbody, hyperbrain” which we will learn more about later on.

Lower IQ is a health risk

If we focus on the lower scores of intelligence, we encounter that it usually goes hand in hand with health problems. And not because of a single reason but for a variety of reasons depending on each specific case.

Sometimes the cause will lie in biological-anatomical problems that may be visible or not (like having less white matter in the brain) and which explain a higher propensity to develop lower IQ and other diseases. Other times, the reasons will be psychological, such as a low IQ that makes it difficult to understand problems and deal with them.

Yet studies indicate that the most common reason will be socioeconomic causes. A lower IQ will oftentimes lead to low-income and/or high-stress jobs that induce chronic stress and offer worse access to good healthcare. Such situations will facilitate the appearance of physical and mental diseases.

On the physical health side, a lower IQ has been found to be associated in different research with more heart, respiratory, and digestive diseases in children. While on the mental side, it is related to a higher probability of developing anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and loneliness. For example, Professor Melby and her team at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology found that borderline IQ (70-85 IQ) had five times more chances of developing a psychiatric diagnosis in comparison to average IQ.

Is high IQ good for your health then?

As we have said before, the general rule of thumb is that the higher the IQ the better health, both physical and psychological. In the words of Professor Koenen from Harvard University, we should talk of a “higher cognitive reserve that protects against neuropathology”. This reserve means that the person with a high IQ has higher brain capacity thanks to higher processing speed -eg. the neurons fire faster- or a better neuronal structure -eg. a higher density of the neuronal dendrites which receive signals from more interconnected neurons than usual-.

A very high IQ will therefore entail a very high level of connectivity between neurons and a strong plasticity that will allow super-fast learning in all or some of the following five domains: psychomotor, sensory, intellectual, imaginational, and emotional. The drawback however, as explained by the “theory of hyperbrain, hyperbody”, is that after a certain threshold such hyperconnectivity will lead to extreme levels of reaction, awareness, and excitability.

If such a person is for most of its life surrounded by positive, secure and growth-fostering persons, the high IQ will become a highly protective factor. But if the person suffers chronic exposure to stressors in a negative situation or context, it could easily lead to a stimulus overload, excessive learning of fear and the development of a ruminative cognitive style.

If that happens, the body will learn to overreact constantly by unnecessarily triggering the activation of the body’s fight-or-flight system, the HPA axis (Hippotalamus-Pituatary-Adrenal Axis). A continuous activation of the HPA axis will in the long run weaken the immune system and create a chronic low-level inflammation of the brain (specially of the prefrontal cortex) that will make it ripe for anxiety, depression and other disorders. A process that also explains why high IQ people have a higher tendency to suffer from allergies.

The risk is even higher if the person has much stronger verbal than quantitative (Karpinski et al. (2018)) or perceptual skills (Kermarrec et al. (2020)), as it seems that the verbally-gifted are more inclined to ruminate and worry endlessly. Apparently, their hyperconnected neuronal networks are so tightly linked with the rest of the brain that they never shut off.

Below you can see a short list from the study of Karpinski et. al (2018) with the relative odds (how many more times likely) for gifted persons to develop a specific disorder in comparison to the average population. Take into account that the study had limitations, including that its gifted sample was limited to persons belonging to Mensa.

- Anxiety disorders: 1.8 times more likely

- Mood disorders (depression, bipolar): 2.8 times more likely

- Attention deficit: 1.8 times more likely

- Asperger: 1.2 times more likely

- Environmental allergies: 3.1 times more likely

Does genetics play a role?

There are very recent genetic studies (like the ones from Shang et al. (2022) and Bahrami et al. (2021)) that lend support to everything we just said. These studies questioned whether, since high IQ and mental disorders are partially heritable, intelligence and mental disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder actually shared genes. They indeed found significant relations in a small group of genes.

For approximately half of the identified genes, if present, the person develops higher IQ and has a higher risk of mental disorder (and the opposite if not present). The other half of genes, if present, the person develops a higher IQ and has a lower risk of mental disorder.

So high IQ will be a risk factor or a protective factor depending on the specific gene mix of each person and the set of circumstances that promote or not their differential expression.

Emotional intelligence and health

So far we have focused on cognitive intelligence, but what about emotional intelligence (EQ), that is, the capacity to perceive, utilize, and manage emotions in one self and others? The few available studies on this topic find that more EQ predicts better mental and physical health in general. It is associated with more exercise and health prevention behaviors. Especially when EQ translates into self-control, sociability, and clarity.

However, when the components of EQ of emotion perception and attention to one’s own emotions are high, the person can experience difficulties processing stress, what could lead to the development of depression. More insensitive individuals, can be perceived as colder by most people, but in exchange are less affected by stress as they process less emotional information of the situation or directly repress it. And that is beneficial in some roles and contexts. You would not want a SWAT police specialist to have its hand trembling when shooting a terrorist with a hostage, right?

An elite university can be a dream or a nightmare

With everything we have learned, we are ready to understand the statistic reported by newspapers that elite universities are plagued by mental health issues in comparison with more average universities. The very high stress burden that elite schools put on the shoulders of highly intelligent individuals is a double-edged sword.

If the student has enjoyed a positive upbringing, social support, and developed a balanced personality, she or he might thrive. But a more perfectionist, lonely, and academically-focused person with negative life experiences will endure a very strong risk of suffering a mental health problem. Sometimes the best university is not the right university.

Quick recommendations

How can we use what we have learned for a better life? In the case of gifted children, it is important to avoid cultivating in them excessive perfectionism and focus on academic matters. Instead promote a balanced approach, rich in sports, creativity, playing, and social activities, which will be more positive, creating a resourceful personality and social support with strong friendships. Even for gifted adults that is a good recipe for starters to turn things around.

In the case of low IQ persons, it is important to discover not just the weaknesses but also the strengths of the person and to try to foster and build upon them a successful life, both socially and in work. For example, a person with a low IQ who is really good in sports, could use that strength to be successful in that area instead of pushing for a more conventional office job, perhaps becoming a sports’ coach, a professional athlete or a sports event manager.

Wrapping up

Through our amazing journey, we have learned that having a higher IQ is usually associated with better physical and mental health. Low IQs are at risk not just because of biology, but specially because of the negative impact that low-income jobs have on quality of life.

Having a very high IQ is also risky. It entails an incredible capacity for learning, but if exposed to the wrong stressful situations it can lead to the chronic activation of the stress system, consequent inflammation of the brain and the development of mental disorders.

Looking into the future, it is obvious that more research is still necessary. Most of the work has focused on the “flashes of lightning” of the gifted, but as Karpinski et. al. (2018) says, we should learn more of the “rumbles of thunder that follow in the wake of brilliance”.

.png)

.png)