We tend to perceive complex behaviors as a sign of intelligence and an advantage for survival. Yet, nature is full of examples of simpler or alternative solutions that are very effective. Animals are indeed provided with amazing acumen and skills that sometimes can even outcompete ours. Analyzing intellectual similarities and disparities we can learn to be more humble and respectful.

Follow me on a journey that will uncover the secrets of intelligence in the animal kingdom. Starting by understanding what intelligence might add to the species’ skillset, exploring ways to measure animal IQ in the lab or, even more importantly, in their natural habitat. Prepare to be astounded by the extraordinary talents of our fellow cohabitants! To conclude, we will look at different specimens and compare their brains with ours. Join us on this expedition to unravel the roots of intelligence! Let’s take a journey into the wild!

Why is intelligence important for species’ survival?

The advancement of human intelligence has reached such a point that we are capable of splitting the most basic molecule of matter, the atom, releasing what many would say is the energy of the universe. Moral dilemmas apart, this knowledge proves a deep understanding of the world. While Oppenheimer is considered a genius, our species would not survive a nuclear disaster… but there are less complex organisms that would. In the broader perspective of evolutionary success, the ideal survival machine is a simple organism. Paradoxically, our intellect could self-inflict our own destruction. Then… is high IQ such a tremendous advantage?

Survival in nature depends on different strategies as prof. Goldstein explains: either a) a species exists in a remarkably stable environment—like the amoeba—or b) it relies on rapid natural selection when its ecosystem changes. In this last group, organisms can adapt via rapid reproduction and mutation—such as bacteria—or, when the breeding rate is slower, they can modify their behavior during their lifetime—e.g., us humans. In its simplest form, intelligence can be seen as the genetic flexibility to adjust our conduct in response to contextual variations. Here we have our first lesson: smartness is just one of the solutions to a species’ success.

How do we measure intelligence in animals?

Intelligence in humans is usually measured with IQ tests. However, animals cannot speak or read, making it difficult to assess their intellectual capacity. Comparative psychologists have ingeniously developed behavior-based tests for evaluating the ability to learn or remember, to count or even to solve problems. Let’s step into the lab and see some examples to understand how researchers measure different aptitudes in various animal species.

General intelligence

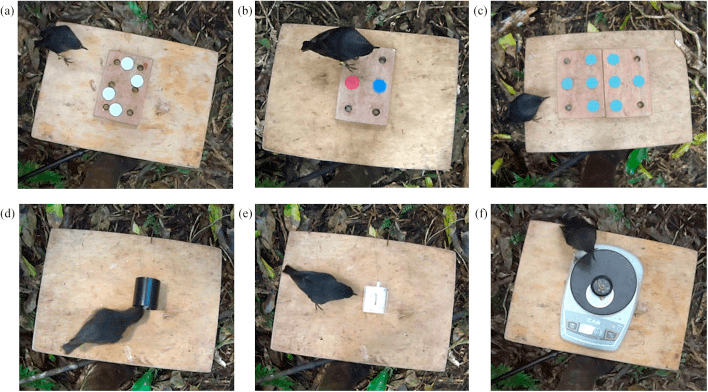

A study by the researchers Shaw, Boogert, Clayton, and Burns (2015) developed a battery of tests to measure different cognitive abilities. We are talking about a whole mental exam but for ribbons. These animals were challenged to find yummy worms by flipping plastic leads (motor test, fig. 1a), recognizing specific colors or symbols (fig. 1b), or even defy their memory by remembering in which of the eight wells their prize was placed (Fig. 1c).

The birds did learn the tasks, but not in the same manner. Those that were better in one of the tests, were usually good in all of them. This is what we call ‘general intelligence’, i.e. the ability to do well on different cognitive areas. Notably, this is a very important property of human IQ.

Self-recognition

The ability to recognize oneself in the mirror is extremely rare in the animal kingdom. One of the few creatures that actually excel at this are dolphins. These marine mammals not only show evidence of self-recognition, but use their reflection to explore parts of their body they are not able to see (such as their mouth’s inside) or to investigate marks that researchers have put on their bodies. Below you can see a very interesting video about it in english.

Moreover, they are able to do so at a younger age than children, as researchers Morrison and Reiss discovered in a study in 2018. This capacity does not reliably emerge in humans until 18-24 months, with the development of self-awareness, including introspection and mental state attribution.

Counting & memory

Looking at our closest relatives, researchers have designed different methods to teach chimpanzees to count from 1 to 9. Chimps are trained to tap the numbers in order to get a reward. Not very impressive right? A 4-year-old can do it!

Researchers realized that these animals could do much more with that knowledge and complicated this task with a memory game. Shall we play it together? Because you are a human I am going to give you a little bit of advantage and explain the test beforehand. In the next video you are going to see the numbers randomly placed on the screen and you have to memorize their positions. Once our primate friend Ayumu knows the order, he will press one and the rest of the digits will be masked… I dare you to try memorizing not until 9, but up to 3. Good luck! Below you can see it in a video in english.

As the director of the study said to a room full of speechless scientists: ‘Don’t worry, nobody can do it’. This amazing short-term (or working) memory might help chimpanzees to survive in the wild, helping them to navigate the branches of huge trees reliably remembering their position.

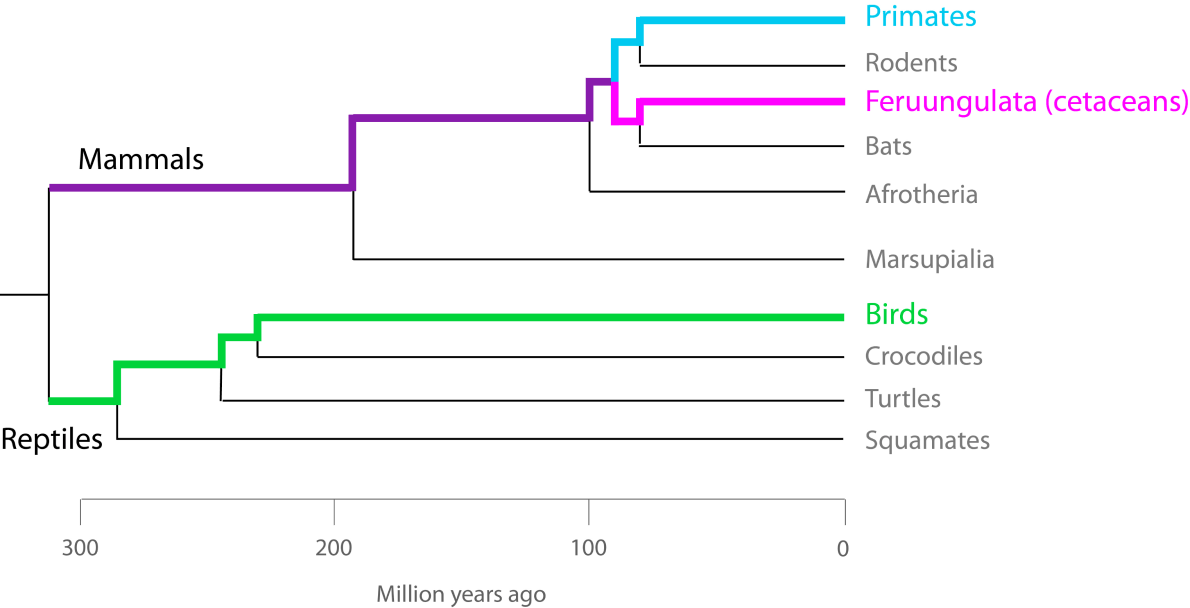

The fact that these animals can perform such astonishing tasks usually leads to the idea that intelligence has grown over thousands of years until peaking at humans. Us, the culmen of evolution, the cherry on the cake, the ultimate brain…However, though…if we analyze the species we talked about and look at an evolutionary tree (Fig. 2), we realize that intelligence did not arise along a single path culminating in the Homo sapiens.

Instead, intellect seems to have emerged independently in birds and mammals. Subsequently, primates and cetaceans also divided from a common ancestor. Thus, it is true that our characteristic set of traits and skills come from a long lineage, yet, parallel forms of intelligence are present in other animal groups. So no, we are not the pinnacle of evolution.

Street-smart is all that counts in nature

Although these capacities demonstrate that animals are provided with an amazing intellect, why would a chimpanzee want to count until 9? What’s the use of measuring a skill that the animal would not use in nature?

A second group of scientist, called behavioral ecologists claim that the most reasonable method to assess brainpower is to judge animals on their street-smart ability to face relevant problems for survival. To be fair, a hungry tiger might not be intimidated by you solving an equation.

We indeed tend to undervalue the exceptional sensory skills of animals when they are of the utmost importance for managing the daily challenges of life. The sense of smell, for instance, gives dogs a whole different perspective of the world. Olfaction, as the team of researcher Kokocińska-Kusiak explains, not only provides information about the current status of the environment but can also allow detection of signals from the past (like the recent presence of preys or enemies). Not even the best human detective would equal such a tracking capacity! Sorry Sherlock.

Another example of formidable powers is the navigational ability of monarch butterflies. During their multigenerational migration, these insects travel from Canada to Mexico, round trip. Such a journey cannot be achieved without a compass, and butterflies do have one. An amazing internal clock helps these animals decipher which direction to go depending on the position of the sun at any given moment. We can try to reproduce the path by using Google Maps… fingers crossed not to lose internet.

We tend to interpret behavior as complex and superior when is more cognitive, but, as in mathematics, the simplest solution is usually the most elegant.

Is our human brain different?

Examining the contrasts in the cognitive abilities of different species, it becomes evident that we hold a distinctive place in the spectrum of cleverness. An important truth about humans is that we have a particularly good abstract intelligence. That is why our definition of intelligence heavily relies on consciousness and logical and conceptual thinking. These qualities, together with the complex use of language are very specific features of our species. Researchers have dug into our brain for decades trying to identify unique structures that could account for such characteristics.

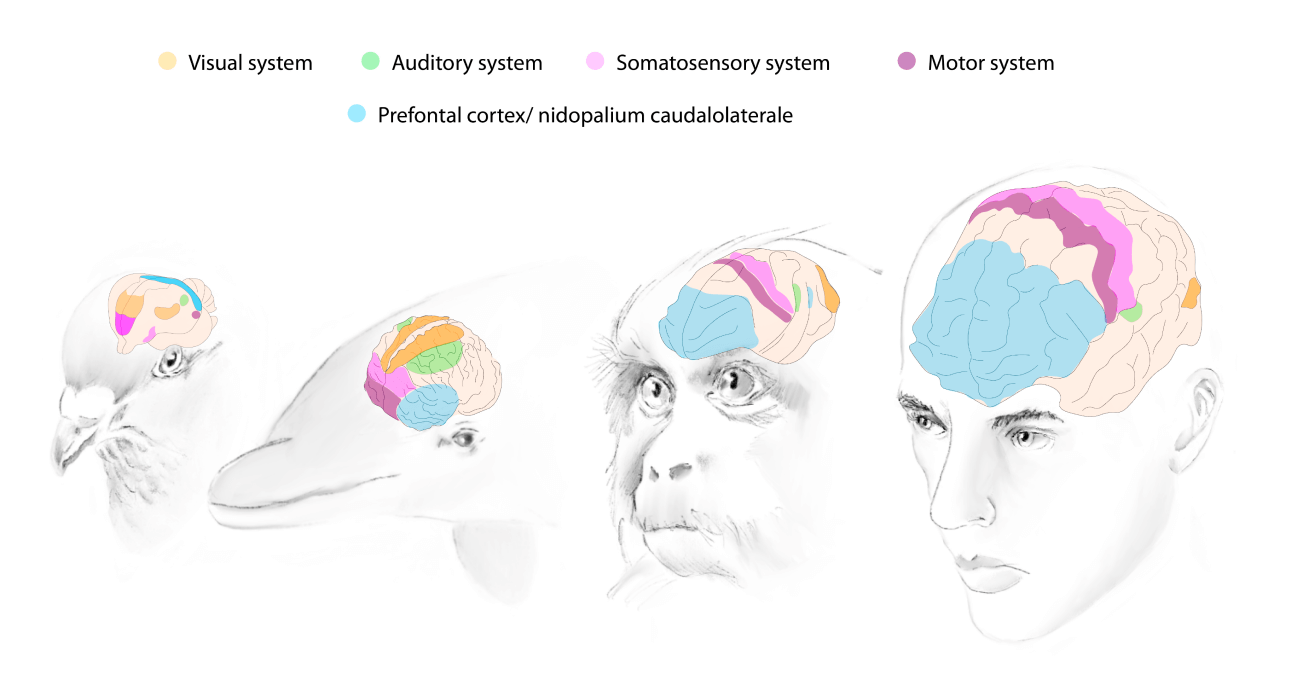

There are, indeed, differences in certain structures when compared with other branches of the evolutionary tree (Fig. 3). However, anatomically the human brain is very similar to that of other primates. Excepting perhaps Broca’s area, which governs speech in people, it seems to be more about subtle differences. A refinement in brain architecture, rather than large-scale alterations, makes us ‘smarter’ than other animals. More concretely, we have more neurons in the cortex; the most superficial layer of the encephalon (from which we have extensively talked in our article about where intelligence is located in the brain), and (2) the insulation of these neurons (myelin) is also thicker, allowing faster communication of the electrical signals (which we explained too in how our intelligence changes with age).

Wrapping it up

If you reached this point I know what you are thinking: this woman is really cheering for ‘team animals’ but it is indisputable that we, humans, have conquered the Earth. And that is completely true. One of the greatest achievements of our species has been, not just to adapt to our environment, but to adapt the environment to us. And that, my friends, has been the key to our success.

Given our lack of strength, speed, or other life-saving attributes, our abstract intelligence has allowed us to design and build a world specifically tailored for us. Such a strategy, as valid as it is, could also become unsustainable in the long run. If the population continues growing at this pace, without changing our societies, natural resources will run out, other species will rapidly disappear, and we will ruin our planet and self-destruct (no need for Oppenheimer’s invention here).

We are intelligent enough to be aware of this reality, let’s prove that we are clever, and let’s respect nature and the amazing diversity of our planet. That’s our winning hand!

.png)

.png)